- raised €11,00

- Day left ENDED

Campaign description

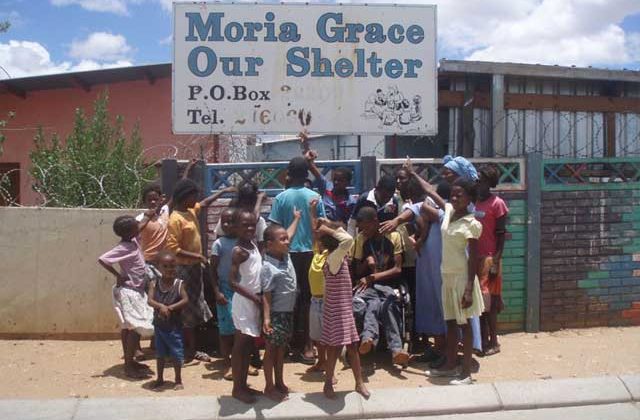

Visiting the Moria Shelter centre

The winter is finally at the end here in Windhoek, the days are longer, the sun is more hot every day and often during the afternoon a warm wind start blowing, carrying sand from the Namib that makes the town appear dusty and mysterious. We heard of a special place and a special person, who dedicates her life to collect, take care and help street children, orphans, children abandoned by everyone… It is the Moria Grace Shelter, and is located in Katutura, the poorest and popular district of the city, the black ex-ghetto in the period before independence, in which now live much of the black population, especially those who are poor.

The winter is finally at the end here in Windhoek, the days are longer, the sun is more hot every day and often during the afternoon a warm wind start blowing, carrying sand from the Namib that makes the town appear dusty and mysterious. We heard of a special place and a special person, who dedicates her life to collect, take care and help street children, orphans, children abandoned by everyone… It is the Moria Grace Shelter, and is located in Katutura, the poorest and popular district of the city, the black ex-ghetto in the period before independence, in which now live much of the black population, especially those who are poor.In this whirl of sand we arrive in Katutura, a little excited. With us there is Maurizio too, a reassuring presence in this mission inside the ghetto, who will document our meeting with his beautiful pictures.

Wilhelmine and the Moria Grace Shelter

It is the second time that we are here. The first time we came to personally meet Wilhelmine, the woman who with courage and tenacity founded and supported the centre since its inception about 20 years ago. Daisry accompanied us, a girl who in the short time that remains free from his work as account manager in an important advertising Namibian company, tries to divulge the “shelter” and helps to raise funds for its support. We met Wilhelmine for the first time a few weeks ago, first of all to understand if everything was “real”, in line with the initiatives that we are trying to bring forward, and then to realize if Scintille could do something useful. We advised her, with a little embarrassment, but with the clarity that distinguishes us: “We are just born, Scintille is young and full of enthusiasm, but we do not have yet enough strength for big projects or donations” And Wilhelmine, kind and sweet answered “It is not the money but love the most important thing and with very little you can do a lot.”

It is the second time that we are here. The first time we came to personally meet Wilhelmine, the woman who with courage and tenacity founded and supported the centre since its inception about 20 years ago. Daisry accompanied us, a girl who in the short time that remains free from his work as account manager in an important advertising Namibian company, tries to divulge the “shelter” and helps to raise funds for its support. We met Wilhelmine for the first time a few weeks ago, first of all to understand if everything was “real”, in line with the initiatives that we are trying to bring forward, and then to realize if Scintille could do something useful. We advised her, with a little embarrassment, but with the clarity that distinguishes us: “We are just born, Scintille is young and full of enthusiasm, but we do not have yet enough strength for big projects or donations” And Wilhelmine, kind and sweet answered “It is not the money but love the most important thing and with very little you can do a lot.”Scintille at Moria Grace Shelter

So today we are coming back and we enter again the dilapidated building, which is definitely in contrast with all the smiles of the children who live in it. It is a really cheerful welcome, as always, everybody run around us, the kids sing their songs while make us visit their single “bedroom”, where they sleep all together. We spend all the afternoon together with this great family. These children are happy and serene, having in Wilhelmine a loving and attentive mother. We deliver to Wilhelmine our “certificate” of donation (with a contribution sufficient to ensure a meal a day for all children for a month), and she’s a little embarrassed, in his difficult English, asking a child to write something for us… The child gives us back the paper where,with infantile calligraphy wrote, “Thank you, we are proud to have someone like you who can take care of us. God bless you”. The same God Wilhelmine is welding her debt to….

So today we are coming back and we enter again the dilapidated building, which is definitely in contrast with all the smiles of the children who live in it. It is a really cheerful welcome, as always, everybody run around us, the kids sing their songs while make us visit their single “bedroom”, where they sleep all together. We spend all the afternoon together with this great family. These children are happy and serene, having in Wilhelmine a loving and attentive mother. We deliver to Wilhelmine our “certificate” of donation (with a contribution sufficient to ensure a meal a day for all children for a month), and she’s a little embarrassed, in his difficult English, asking a child to write something for us… The child gives us back the paper where,with infantile calligraphy wrote, “Thank you, we are proud to have someone like you who can take care of us. God bless you”. The same God Wilhelmine is welding her debt to….The Moria Grace Shelter

The Moria Grace Shelter is located in the popular district of Katutura, Windhoek, Namibia. Currently it hosts 33 children of all ages. The younger, arrived only a few weeks ago. She has a small and smiling small face, despite the life from her early days was not very tender with her … She was found near a box of rubbish, where she was abandoned immediately after the born. It has a name that wishes a magical destiny but is unpronounceable in its original Damara language: it means “the one who is born twice.”

The Moria Grace Shelter is located in the popular district of Katutura, Windhoek, Namibia. Currently it hosts 33 children of all ages. The younger, arrived only a few weeks ago. She has a small and smiling small face, despite the life from her early days was not very tender with her … She was found near a box of rubbish, where she was abandoned immediately after the born. It has a name that wishes a magical destiny but is unpronounceable in its original Damara language: it means “the one who is born twice.”The other kids are really of all age groups, from pupils to adolescents.

There are so many different children, housed at Moria Grace: street children living under bridges or in sewers, gathered in the street to give them a place to live and the opportunity to go to school; orphans and abandoned children, children whose parents are in prison, living with distant relatives who don’t take care of them or coming from villages or farms where they had no chance to go to school. All children now have the opportunity to go to school. When they grow up, the centre organizes fundraising to pay professional courses that will help children to enter the world of the work.

What we can do: some numbers

Scintille may continue to contribute to the sustenance and development of this centre, with other initiatives, including ones targeted to specific projects.

Scintille may continue to contribute to the sustenance and development of this centre, with other initiatives, including ones targeted to specific projects.

We want to share with you some “numbers”, only two examples which we believe are significant:

– With 110 euros all children currently housed in the centre can eat once a day for a month

– With 50 euros may be given to a teenager the opportunity to attend a vocational course for the use of the computer, and so letting him enter more easily into the world of the work.

Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: the beginning

Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: the beginning

Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: the beginning

I was born in Aranos on 5 May 1958. My mother was very poor and had not studied. Our life was difficult and were barely able to survive. We had some relatives living in Windhoek who often visited us. Every time my cousins came to our house, with their beautiful clothes and beautiful cars, I thought that life in Windhoek had to be really beautiful. In those moments I thought that one day I would go in Windhoek, I could work and earn money to take care of my mother.

This was what I did. It was 1976 when I arrived in Windhoek. I went to live in Katutura, right in front of the Lutheran church. Those were the days when all non-whites had to carry a pass; without it you could not live with anyone in Windhoek if you were from outside of the area. I then realised that it would not be easy to live in Windhoek. The police always arrived early to raid people’s houses to check whether there were any ‘illegals’ living there. We used to warn each other by ‘greeting’ so that we were not caught by the police.

To avoid being caught by the police, we used to tie ourselves with ropes underneath the beds. The police then used to come and pull the beds away from the wall, to see if anyone was hiding. We were tied to the bed, and the police could therefore not discover us. That way we used to be able to fool them. Every morning, it was the same routine.

Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: Martha

Scintille Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: Martha

Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: Martha

I had a friend, Martha who was from Maltahohe. One day she said that someone told her that we should go to the big rubbish dump in Kupferberg (which was a strange place to me). Apparently it was very peaceful there. I thought that Kupferberg was a farm. We walked through Pioneerspark to the dump.

When we reached Kupferberg, I realised that it was much worse than being raided by the police in Windhoek. There were no water and we had no clothes or even underwear. We used to dig holes and fill it with newspapers to keep us warm. When we arrived at Kupferberg, there were already many people who did not have passes.

We used to make clothes with newspapers and to eat the food that was rotten and thrown away at the dump. The stench at the dump was unbearable, but we were able to sleep in peace without being raided by the police.

The problem at the dump was that often when refuse was thrown away, there were big blankets amongst the rubbish. This, we discovered were the bodies of dead babies, small children and women. When these blankets were dumped, we used to think that it contained food, only to make this grisly discovery.

There was no water, and when it did not rain for long periods we had nothing to drink.

The old people at the dump never abused us sexually, but often when the rich white men came to the dump, they abused us. Sometimes they even killed the girls. I do not know why the rich men used to beat us whenever they saw us at the dump.

When they were, to avoid being killed, we had to smile and allow them to abuse us, so that saving our lives. Often it was more than one man at a time who abused us. My body was almost permanently in pain.

My friend Martha, who took me to the dump initially, eventually died there. That day I remember a white car that drove very slowly towards the dump. When we saw the car, we ran away. Martha was very big and could not run very fast. The men in the car caught her and raped her several times. After they were done, they left her dying on the road.

When they left, we went to her rescue. She was badly wounded and knew would not survive for long. She begged us to go back to our homes so that no-one could hurt us again. We tried to move her to a better place on the dump, but she died within three days.

It was then I decided that I would not hide any longer. I cried very loudly and did not care that someone would come and kill me too.

Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: the rebirth

God was very gracious and at that time an old white lady came to the dump. She was very kind and used to ask us to collect and break car batteries so that she could use some of the inside parts. She always used to bring fresh mieliepap that we were very grateful for.

God was very gracious and at that time an old white lady came to the dump. She was very kind and used to ask us to collect and break car batteries so that she could use some of the inside parts. She always used to bring fresh mieliepap that we were very grateful for.I later shared my experience with the old lady and told her about Martha’s death. She then told me to get into the boot of her car and took me to her home. There were no raids at the houses of the whites, and she took care of me very well. I worked hard in her home, but she also had to later leave Windhoek. She then ‘gave’ me to another family because I was so hardworking. I lived there for many years, mainly because there was no issue about a pass with them.

During all this time, I always used to think about caring for children, because God was very gracious to me while I lived at the dump. The money that I earned was very little, and I wanted to save up to care for my mom and vulnerable children . When I was off-duty, I resorted to sex trade in order to save money, which I kept in cool drink cans. What I saw at the dump, kept the desire burning within me to take care of children.

My biggest desire was to get a house so that I could take care of children. I always thought of those bodies of children found in the dump. On weekends I used to go to the dump to find out whether there were any children’s corpses found. I could see that the racial division kept people apart and bred much hatred amongst them.

Coming back from the weekend, I used to tell that I really wanted a house. Everybody then used to ask me how I would afford it with my little money, but I was determined to save money in any way I could. I used to listen to the radio and often heard how children went missing or was killed; those times I really blamed myself for not having a house to take care of these children.

Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: the project

I went on like this, working and saving until I arrived to have 25 cans full of money. I went to the municipality to apply for a house. A man told me to fetch a more senior person, because I was too small to get a house. I then told him that I would be prepared to offer him sexual favours in exchange for a house, to which he agreed. I did not care about myself; all that was continually in my mind was how Martha and the children were murdered at the dump And so I obtained my first one bedroom house.

I went on like this, working and saving until I arrived to have 25 cans full of money. I went to the municipality to apply for a house. A man told me to fetch a more senior person, because I was too small to get a house. I then told him that I would be prepared to offer him sexual favours in exchange for a house, to which he agreed. I did not care about myself; all that was continually in my mind was how Martha and the children were murdered at the dump And so I obtained my first one bedroom house.

I started gathering children whose mothers were working, and only asked them to contribute one cup of flour and one cup of sugar per day. I was the only one in a black township who did something like that. I named the centre Sonop Shelter. Some of my neighbours went to Welfare services and laid a complaint against me. Welfare services then held a meeting and came to Sonop where they came to see me.

The persons who attended the meeting were all very well dressed and seemed important. They asked me for my documentation and permission to take care of children at my home. During all this time I kept silent and just listened to them. When they were done, I lifted my right hand to them and said that it was my certificate. I explained to them that I promised God that I would always take care of children. After that meeting, welfare workers began their investigation on me.

Wilhelmine Afrikaner’s story: the shelter

Fortunately, some people from the private sector also attended the meeting. One of them was Mrs Trubody who was a very compassionate woman. She pointed out that the children were happy and that the shelter was very clean. She then urged them to support me instead of trying to close me down. With her help a large sleeping room was built that was used by the kids, to this day.

Fortunately, some people from the private sector also attended the meeting. One of them was Mrs Trubody who was a very compassionate woman. She pointed out that the children were happy and that the shelter was very clean. She then urged them to support me instead of trying to close me down. With her help a large sleeping room was built that was used by the kids, to this day.I encouraged more mothers in the area to start day care centres to provide for children of working mothers. I then used to go around these houses to see what was happening there and if everything was all right.

I did not start this work to compete with anyone, but with the sole purpose to prevent the things that happened to me. I did not want to earn money, but children’s day-care was an absolute necessity in our black township. That way the children were safe and loved. Later I changed the name to Moria Grace.

Thus was born the shelter, which today is called “Moria Grace Shelter” and that he is doing his work now for more than 20 years.